Bank Swallows and Motorsports:

In the race to save species at risk, we need to pick up the pace

This story, like many that deal with species at risk in Canada, is a long one. It deals with a proposed race track, federal and provincial law, a bird, and, like many other species at risk stories, it is still ongoing, despite 16 years and numerous legal challenges. To begin, we go back to 2005 when a group of Calgary businessmen (“Badlands Motorsports”) bought a parcel of land in the Rosebud River Valley to build a racetrack.[1] Since then, the area has been involved in multiple ongoing legal disputes, in large part over a very small bird – the Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) which is an aerial insectivorous bird that nests in colonies on vertical cliff faces, along banks along waterbodies, and in human-made habitats, including along the banks of the Rosebud River.[2] It has been the subject of numerous court hearings ranging from the Environmental Appeals Board through to the Federal Court. Recently a proposed recovery strategy for the bank swallow was released, potentially impacting upon the future of development in the area.[3]

After purchasing the land in 2005, Badlands Motorsports started the approval and development process. They worked with Kneehill County to approve an Area Structure Plan in June 2013 and later all subdivision approvals and development agreements were finalized with the County.[4] In 2020, Badlands Motorsports received Water Act and Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act approvals, approving the fill in and modification of multiple wetlands and the construction and operation of a storm drainage system.[5] However, despite each of these successful steps, litigation over the area continued into spring 2021. This is where the Bank Swallow comes in.

The Bank Swallow and the SARA

The Species at Risk Act (“SARA”) is the federal Act whose purpose is to “prevent wildlife species from being extirpated or becoming extinct, to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity and to manage species of special concern to prevent them from being endangered or threatened.”[6] It does this through the use of species monitoring and assessment; species and habitat protection provisions; and recovery strategies unique to each listed species. It is important to note that SARA prohibitions, at least in the first instance, apply primarily to federal lands, aquatic species, and migratory birds – covered under the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994 (“MBCA, 1994”) – of which the Bank Swallow is one.[7] At the provincial level, species at risk are managed under the Wildlife Act which, while originally written as a piece of hunting legislation has since been expanded to include some prohibitions and area-based protection, including provisions for the designation and limited protection of endangered species and their habitat.[8] The Bank Swallow is not listed as a species at risk provincially, although it was identified as sensitive in 2015 (see here).

Under the SARA, recommendations for the classification of species at risk are made by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (“COSEWIC”).[9] COSEWIC assesses Canadian species, classifying them under one of the ‘Categories of Species at Risk’ and in 2013, COSEWIC classified the Bank Swallow as threatened.[10] This classification, if adopted by the Minister, sets off a chain of events, the first of which is the requirement for the Minister to prepare and publish a strategy for the species’ recovery within two years of classification.[11] In this case, the Minister approved the Bank Swallow’s classification as threatened in November 2017, four years after COSEWIC’s recommendation and from there the countdown to the required recovery strategy began.[12] Specifically, SARA requires a recovery strategy to address any threats to the survival of the species, including any loss of habitat and to include:[13]

- a description of the species and its needs;

- an identification of the threats to the species and its habitat

- an identification of the species’ critical habitat or (c.1) a schedule of studies to identify critical habitat; and

- a statement of the population and distribution objectives to assist in recovery.

Based on the recovery strategy, the Minister must prepare an action plan, identifying the species’ critical habitat, including any activities likely to result in its destruction.[14] It must also include a statement of proposed measures to protect the species’ critical habitat and an identification of any portions of the species’ critical habitat that have not yet been protected.[15] 180 days after critical habitat has been identified, whether through a recovery strategy or action plan, all of the critical habitat is to be protected.[16] However, the ability to actually do so is limited and is discussed in more depth below.

Spring 2021: Skibsted v Canada (Environment and Climate Change)

The original deadline for the recovery strategy for the Bank Swallow was November 2019; however, despite this legal requirement, by spring 2021 no recovery strategy had been released. In response to this delay, a federal court challenge was brought by numerous landowners living in the Rosebud River Valley (the “Landowners”). The Landowners brought an application for judicial review seeking an order of mandamus which would compel the Minister of Environment and Climate Change (“ECCC”) to prepare and publicly register the required recovery strategy and action plan and to designate critical habitat for the Bank Swallow.[17] Specifically, the Landowners sought a writ of mandamus that would compel the Minister to:[18]

- prepare a recovery strategy for a species known as the “Bank Swallow” pursuant to section 37(1) of the Species at Risk Act (“SARA”);

- prepare an action plan or action plans based on the recovery strategy pursuant to section 47 of SARA;

- to recommend, identify and/or designate critical habitat for the Bank Swallow pursuant to sections 41(1)(c), 58(5) and (5.1) of SARA; and

- recommend that the federal Cabinet make an Emergency Order providing for the protection of the Bank Swallow pursuant to section 80(1) of SARA, particularly in or around the lands subject to Water Act, RSA 2000, c W-3, Approval No. 00406489-00-00.

They also sought an interlocutory injunction against Badlands Motorsports – an interlocutory injunction would stop them from proceeding with any construction or development before the application could be heard and ruled upon; although that motion was dismissed.[19]

While ECCC acknowledged the legal requirement to prepare a recovery strategy, they argued that any delay was reasonable due to the complex nature of the file and did not warrant judicial intervention.[20] ECCC also argued that the request for an action plan was premature because the recovery strategy, and subsequent comment period, must occur before any requirement for an action plan under SARA is triggered.[21]

The legal test for mandamus requires that the applicants (in this case the Landowners) demonstrate that there is a public legal duty to act and that this duty is owed to the applicant.[22] There are two ways to determine that a public legal duty is owed – the first is that the Landowners are found to be directly affected and second is that if they are not found to be directly affected, they are found to have public interest standing. The Federal Court of Appeal held that to be “directly affected” by a decision the decision must have affected the legal rights, imposed legal obligations on, or prejudicially affected the party bringing the application for judicial review in some way.[23] In this case, the Court found that without a final Strategy it was not yet known whether the Landowners’ properties would be affected by protections for the Bank Swallow and therefore any finding of directly affected status was premature.

The second option would have been to find that the Landowners had public interest standing. In order to find public interest standing the court must consider three factors: (1) whether there is a serious justiciable issue raised; (2) whether the plaintiff has a real stake or a genuine interest in it; and (3) whether, in all the circumstances, the proposed suit is a reasonable and effective way to bring the issue before the courts.[24] While the Court acknowledged that there is no bar to individuals being granted public interest standing, the Landowners in this case did not pass the three-part test for public interest standing.[25]

In the end, the Court agreed with ECCC, finding that any mandamus relief was premature because the duty to issue an action plan or protect critical habitat was only triggered after the final recovery strategy was posted.[26] The Court also found that the Landowners were not directly affected because while there was no dispute that the Bank Swallow has colonies in the Rosebud River Valley, at the time of the application, there was no certainty that some or all of the Landowners’ properties would be designated as critical habitat.[27] The Court also noted that if a mandamus order had succeeded, it would only have required that the recovery strategy be posted by June 30, 2021. This relied, in large part, on ECCC’s evidence that work was being completed on the strategy and that they anticipated it would be posted in June 2021.[28] Despite this, the Court did remind the ECCC that going forward “the remaining steps of the statutory process to protect that threatened species are [to be] effected without further delay.”[29]

The Long-Awaited Recovery Strategy

A proposed (i.e. draft) Recovery Strategy for the Bank Swallow (the “Strategy”) was finally posted in June 2021.[30] It notes that while multiple factors are having a cumulative impact on the species, the most likely primary threat to the Bank Swallow is “the broad-scale ecosystem modifications in the breeding, migration, and wintering areas of the species resulting in less abundant invertebrate prey.”[31] The Strategy goes on to provide examples of activities that are likely to result in the destruction of critical habitat and identifies certain activities that can lead to the destruction of both nesting habitat and foraging habitat.[32] Specifically, the destruction of critical nesting habitat can occur due to activities including:[33]

- the alteration of the topography composition or erosion processes of the bank or bluff or permanently blocking access to nesting habitat;

- activities that result in a direct loss of bank or bluff habitat through its conversion to an incompatible land-use including commercial use and which could occur due to replacing the bank with a hard surface or changing the bank slope angle to less than 70 degrees; and

- changes in the hydrological regime that alters water levels.

The destruction of critical foraging habitat can occur due to a number of activities including:[34]

- activities that result in the removal of biophysical attributes of foraging habitat including commercial activities;

- activities that result in the degradation of foraging habitat including insecticides and pesticides and soil contamination; and

- the permanent removal of hedgerows, shelterbelts, wetlands, marshes or adjacent land.

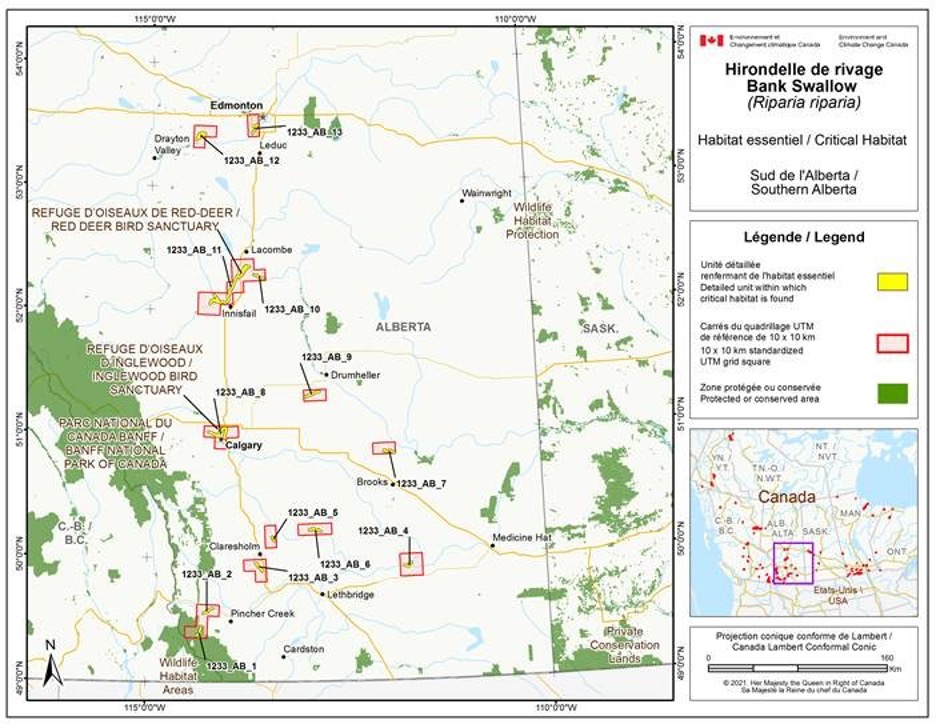

The Strategy also specified certain threats including housing and urban areas, commercial and industrial areas, mining and quarrying, roads and railroads, dams and water management/use, as well as other ecosystem modifications.[35] Specifically, new residential, commercial, or industrial development should avoid removing any nesting habitat.[36] In total, the Strategy identified 15 areas of critical habitat in Alberta, including the Rosebud River – pictured at 1233_AB_9 and circled in the image below.[37]

Figure 1: Critical Habitat for Banks Swallow in Southern Alberta (in yellow shaded polygons) (Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2021)[38]

Now that the proposed Strategy has been released, a 60-day comment period begins. Thirty days after the expiry of this period, the Minister is required to publish the final Strategy.[39] This means a final Strategy should be released by October 2021.

What does all this mean for the Rosebud River Valley Bank Swallow?

Since the Strategy has not been finalized, detailed predictions about how it may or may not affect the Badlands Motorsports project are premature; however, it is interesting to consider what could happen if the Bank Swallow habitat in the Rosebud River Valley is classified as critical habitat. This is particularly notable because already, the Badlands Motorsports project has released documented plans for the destruction of wetlands, the alteration of banks or bluffs, and the direct loss of a bank or bluff, all of which are included as types of critical habitat in the proposed recovery strategy.

In addition to certain possible critical habitat protections, the SARA is meant to protect individuals and to recover populations of species at risk (species of special concern, and threatened, endangered, or extirpated species). As such, SARA prohibits the killing, harming, harassing, capture or taking of listed species.[40] It also prohibits the damage or destruction of a residence of a listed species.[41] These prohibitions protect the individual birds and their residences but do not protect their critical habitat on a larger scale. To achieve that goal, critical habitat protections need to be deployed.

One such provision is section 58(1) which states that no person shall destroy any part of the critical habitat of any listed endangered species or any listed threatened species if the listed species is a species of migratory birds protected by the MBCA, 1994.[42] However the protection afforded by section 58(1) only applies (if the critical habitat relates to lands other than certain federal lands) to the extent ordered by the Governor in Council on the recommendation of the Minister.[43] So, while there is an obligation to make a recommendation if the Minister is of the opinion that “there are no provisions in, or other measures under, this or any other Act of Parliament, including agreements under section 11, that legally protect any portion or portions of the habitat to which that Act applies” it would require action to be taken even after critical habitat was identified.[44] Specifically, once critical habitat is identified in the Strategy or subsequent action plan, a cabinet order designating the area as critical habitat for the purposes of section 58(1) would still be required. Potentially further confounding protection for the Bank Swallow is that section 58 of the SARA states that protection of critical habitat “applies only to those portions of critical habitat that are habitat to which” the MBCA, 1994 applies.[45] A major deficiency of the MBCA,1994 is its limited consideration of habitat, focusing rather on protection of nests and individuals. In this regard, even if section 58 protections were to apply, it may simply reflect further protection for the Bank Swallow nests.

Another tool for the protection of critical habitat is found in section 80 of the SARA – known as the emergency order provision. Section 80 enables the Governor in Council to issue emergency orders, extending the SARA’s protections to a particular species, and all of its critical habitat, regardless of whether that habitat is located on federal or provincial land.[46] In the case of a species of migratory birds, section 80(1)(b) applies. 80(1)(b) states that if habitat is situated on land other than federal land, the Minister can identify habitat that is necessary for the survival or recovery of the species in the area and include provisions requiring the doing of things that protect the species and provisions prohibiting activities that may adversely affect the species and that habitat.[47] Again, this would require a secondary step after the initial identification of Bank Swallow critical habitat. To date, emergency orders have only been used in two instances – for the greater sage-grouse and the western chorus frog.[48]

In addition to the SARA, protections exist under the MBCA, 1994. This Act implements the Migratory Birds Convention (an international convention) and is designed to prevent harm to those migratory bird species listed in Schedule Section 2 to the Act.[49] In addition to imposing restrictions on hunting, regulations under the Act prohibit the disturbance, destruction or taking of a nest, egg, or nest shelter, or the possession of a live or dead migratory bird, nest or egg whether through direct action or through an incidental take.[50]

All of this is to say that, even after a final Strategy is released, the full protection of critical habitat in the Rosebud River Valley will require further action. In the meantime, the Badlands Motorsports project can move forward, particularly since they have received the other required approvals. However, they would do so at significant risk if the project is likely to impair or destroy Bank Swallow nests (or critical habitat). This could be a riskier endeavour because of the possibility for later federal intervention in the area. Despite this risk, it remains to be seen how the federal government will act after the comment period for the draft Strategy has lapsed and whether further protections will be put in place for the Rosebud River Valley Bank Swallow.

Unfortunately, this story provides yet another stark example of the potential impacts of delayed action on a species at risk. The slow production of recovery strategies (and the knock on effects on action plans) under SARA has real world implications, and yet delay in species at risk management appears to be the general approach for governments (see other blog posts about the woodland caribou, greater sage-grouse, and orca whales). Delays in protecting habitat, for a species at risk, can mean the difference between survival and recovery and extirpation (or extinction). If there is a need for racing, the race should surely be for effective habitat protection.

[1] Justine Hunter, “A racetrack a songbird and the battle over the future of the Rosebud River Valley” (11 July 2021) The Globe and Mail online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/british-columbia/article-a-racetrack-a-songbird-and-the-battle-over-the-future-of-the-rosebud/.

[2] Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2021. Recovery Strategy for the Bank Swallow (Riparia riparia) in Canada [Proposed]. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa. ix + 122 pp [Recovery Strategy for the Bank Swallow].

[3] Alberta Environment and Parks, Approval No. 00406489-00-00 (8 January 2020) online: https://avw.alberta.ca/pdf/00406489-00-00.pdf [AEP Approval No. 00406489-00-00]; Alberta Environment and Parks, Approval No. 462694-00-00 (27 February 2020) online: https://avw.alberta.ca/pdf/00462604-00-00.pdf [AEP Approval No. 462694-00-00]; Skibsted v Canada (Environment and Climate Change), 2021 FC 416 [Skibsted v Canada].

[4] County of Kneehill, by-law 1597, Badlands Motorsports Resort (June 2013).

[5] AEP Approval No. 00406489-00-00, supra note 3; AEP Approval No. 462694-00-00, supra note 3.

[6] Species at Risk Act, SC 2002, c 29, s 6 [Species at Risk Act].

[7] Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994, SC 1994, c 22 [MBCA].

[8] Wildlife Act, RSA 2000, c W-10; Shaun Fluker & Jocelyn Stacey, “The Basics of Species at Risk Legislation in Alberta” (2012) 50:1 Alta L Rev 95 at 97 [Fluker & Stacey].

[9] Species at Risk Act, supra note 6, s 15(1).

[10] Recovery Strategy for the Bank Swallow, supra note 2 at s 1.

[11] Species at Risk Act, supra note 6, s 37(1).

[12] Order Amending Schedule 1 to the Species at Risk Act, SOR/2017-229.

[13] Species at Risk Act, supra note 6, s 41(1).

[14] Ibid, ss 47 & 49(1)(a).

[15] Ibid, ss 49(1)(b) & (c).

[16] Ibid, ss 57 & 58.

[17] Skibsted v Canada, supra note 3 at para 1.

[18] Ibid at para 10.

[19] Ibid at para 12.

[20] Ibid at para 52.

[21] Ibid at para 53.

[22] Ibid at para 48.

[23] Ibid at para 76.

[24] Ibid at para 87.

[25] Ibid at paras 94 & 95.

[26] Ibid at para 57.

[27] Ibid at para 83.

[28] Ibid at para 129.

[29] Ibid at para 129.

[30] Recovery Strategy for the Bank Swallow, supra note 2.

[31] Ibid at s 4.2

[32] Ibid at Table 8.

[33] Ibid at Table 8.

[34] Ibid at Table 8.

[35] Ibid at Table 8.

[36] Ibid at s 6.3.

[37] Ibid at s 7.1.3.

[38] Ibid at Fig E-15.

[39] Species at Risk Act, supra note 6, ss 43(1) & (2).

[40] Ibid, s 32.

[41] Ibid, s 33.

[42] Ibid, s 58(1).

[43] Ibid, s 58(5.1); Fluker & Stacey, supra note 8 at 109.

[44] Species at Risk Act, supra note 6, s 58(5.2)(a)

[45] Ibid, s 58(5.1).

[46] Ibid, s 80.

[47] Ibid, s 80(1)(b)(ii).

[48] Emergency Order Amending the Emergency Order for the Protection of the Greater Sage-Grouse (Miscellaneous Program), (2017) C Gaz II, 1256 (Species at Risk Act); Emergency Order for the Protection of the Western Chorus Frog (Great Lakes/St. Lawrence – Canadian Shield Population), (2016) C Gaz II, 682 (Species at Risk Act).

[49] MBCA, supra note 7.

[50] Migratory Birds Regulations, CRC, c 1035.

ABOUT THE ENVIRONMENTAL LAW CENTRE:

The Environmental Law Centre (ELC) has been seeking strong and effective environmental laws since it was founded in 1982. The ELC is dedicated to providing credible, comprehensive and objective legal information regarding natural resources, energy and environmental law, policy and regulation in Alberta. The ELC’s mission is to educate and champion for strong laws and rights so all Albertans can enjoy clean water, clean air and a healthy environment. Our vision is a society where laws secure an environment that sustains current and future generations.

As a charity, the Environmental Law Centre depends on your financial support. Help us to continue to educate and champion for strong environmental laws, through tools such as our blog and all of our other resources, so that all Albertans can enjoy a healthy environment. Your support makes a difference.

Donate online today