Inside this blog

- A review of the existing Edmonton’s River Valley Area Redevelopment Plan with a look at challenges and legal gaps

- The improvements of the draft ARP and some concerns

- Recommendations

Written by Simon Robertson and Kyra Leuschen.

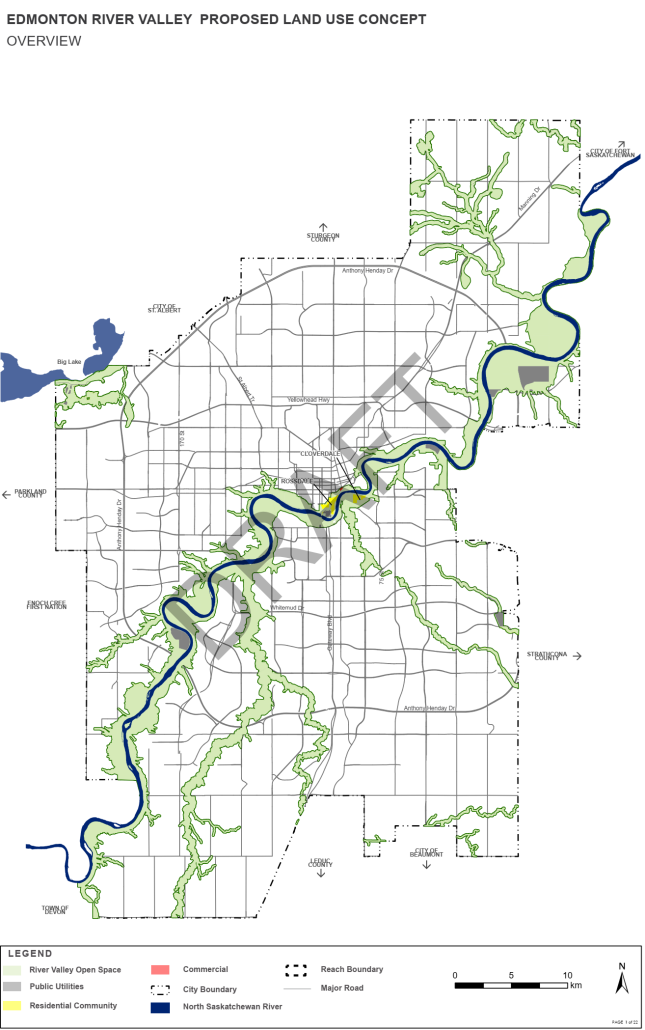

The North Saskatchewan River Valley Area Redevelopment Plan (Bylaw No. 7188) (the ARP) is a bylaw intended to protect the North Saskatchewan River Valley and Ravine System from development.[1] The City of Edmonton is currently modernizing the ARP and released a Draft Area Redevelopment Plan for public review and consultation.[2] While the Draft ARP is a marked improvement over the existing ARP, it continues to grant considerable discretion to City Council to permit development in Edmonton’s river valley. This begs the question – what, if any, new or expanded development should be permitted in Edmonton’s river valley?

The Existing Area Redevelopment Plan (ARP)

In its current format, the ARP screens projects by requiring anyone developing a major public facility to complete an environmental impact assessment (EIA) and a location study. A major public facility is a major facility, which is any development classified in the Edmonton Land Use Bylaw as basic services, community, educational, recreational and cultural services, or natural resources, that is either publicly owned or developed on public lands.[3] All major public facilities require an EIA to be completed, but it does not require approval. The location study must explain why the proposed river valley location is essential (i.e., why the project cannot be moved elsewhere) and needs to be approved by City Council. This approval enables the development in question to proceed.

However, the ARP has three primary issues. First, it does not require private projects to obtain City Council approval (although approval under other bylaws may still be necessary). Second, what makes a river valley location “essential” is undefined and therefore entirely at the discretion of City Council. Furthermore, a court is unlikely to instruct Council on how to weigh competing factors (e.g., environmental and economic benefits) in the approval process.[4] Third, although an EIA is mandated, there is no point at which a development project must be denied because of its environmental damage. In other words, as long as the EIA is completed (along with the essential location study), a project can proceed regardless of its consequences.

More generally, under the current ARP, environmentally harmful projects do not always require City Council approval, Council has the discretion to consider whatever they would like when approving a project, and there is no baseline environmental standard a project must meet.

Some of the deficiencies in this process were laid bare in the decision of Edmonton River Valley Conservation Coalition Society v Council of the City of Edmonton. Under the existing ARP, EPCOR wanted to build a solar farm in the river valley, requiring rezoning and an ARP amendment to proceed. City Council completed both. The Edmonton River Valley Conservation Coalition (ERVCC) brought an application for judicial review of the council amendment. The issue was whether the solar development constituted a major public facility under the ARP. If so, the City Council was required to approve the development’s location study before rezoning. They had not done so. Additionally, the ERVCC alleged that the City Council improperly emphasized the project’s financial benefits in their decision-making.

Despite the City of Edmonton (a public entity) being the sole shareholder of EPCOR, the Court found that the solar development did not constitute a major public facility.[5] Therefore, an essential location designation was unnecessary. Furthermore, the Court stated that even if an essential location designation were necessary, it would be improper for the judiciary to instruct the City Council on how to weigh competing factors when making decisions because, among other reasons, “there is nothing in [the ARP] that requires equal weighting of the factors.”[6] This outcome demonstrates the inadequacy of relying on judicial review to ensure the environmental objectives underpinning the ARP are met. As a corollary, it highlights the importance of a well-defined, prescriptive River Valley ARP to ensure adequate environmental protection.

The New Draft ARP

The new Draft ARP aims to “ensure the environmental protection of” and “provide public access to” Edmonton’s river valley.[7] The primary land use throughout the Plan area shall be open space and developments on lands designated for River Valley Open Space or Public Utilities (this is nearly the entire river valley) shall be limited to those that are compatible with environmental protection, recreation, and cultural heritage, or provide transportation or utility services that require a river valley location.[8] The Draft ARP also directs the City to pursue City ownership of lands in the Plan area and dedicate eligible lands as an environmental reserve through the subdivision process.[9]

The Draft ARP provides that existing residential land uses, public utility infrastructure, transportation infrastructure and agricultural uses may continue. Development of new or significantly expanded intensive open space facilities, intensive utility facilities, intensive transportation facilities (all defined in the Draft ARP), and development in the floodplain are discouraged. Meanwhile, subdivisions that would prohibit future dedication of reserves in the Plan area, applications for rezoning (other than those compatible with open space, agriculture or utility uses) within 30 m of a watercourse, modification of waterbody boundaries (with some exceptions), applications to rezone river valley lands under agriculture use, and zoning to allow new or significantly expanded industrial uses (such as natural resource development) shall not be approved.

Under the Draft ARP, all development proposed on land designated as River Valley Open Space or Public Utility must complete a strategic assessment and an environmental assessment.[10] Although the Draft ARP does not provide a clear timeline, the strategic assessment likely occurs first because it sometimes requires City Council approval. Meanwhile, the environmental assessment is generally not completed until “later project stages.”[11]

The strategic assessment must explain the anticipated benefits of a project, its alignment with any relevant City planning documents, and the necessity of a river valley location while also providing an overview of the project’s potential environmental impacts and any public engagement.[12] If a project is a new or significantly expanded intensive utility, transportation, or open space facility, or is a new or significantly expanded development likely to have permanent, adverse environmental or community impacts that cannot be mitigated, the strategic assessment needs City Council approval before the project can continue.[13] In deciding whether to approve a strategic assessment (and therefore a project), the City Council must consider whether the proposed development requires a river valley location, whether it is in the public interest, and whether it meets the goals, objectives, and policies of the Draft ARP.[14]

Meanwhile, rather than functioning as a screening mechanism, the environmental assessment is intended to gather information and support mitigation of adverse environmental impacts. It must address the project’s environmental impacts and how they will be mitigated, any environmental monitoring requirements, and any feedback from engagement with the public, stakeholders, or Indigenous groups.[15] The environmental assessment never requires City Council approval (although it does require review and acceptance by the department responsible for river valley strategic planning).

Existing ARP vs the Draft ARP

The Draft ARP is an improvement upon its predecessor. It articulates a clearer vision for protection and development in the river valley. Most new or significantly expanded development requires a strategic assessment and the approval of the City Council to proceed. The Draft ARP also provides a list of factors the City Council must consider before granting its approval. Certain types of development are outright prohibited and discouraged. Still, while the Draft ARP uses a different language than its predecessor, it retains some of the issues around discretion and ambiguity in how decisions must ensure the conservation of the river valley. For instance, the Draft ARP does not require the following types of projects to obtain City Council approval:

- Small Projects – while new or significantly expanded intensive utility, transportation, and open space projects generally require approval, projects are exempt if they are small enough.[16] This exemption incorrectly equates a project’s physical size with its negative environmental impact, which can still be substantial, especially if several smaller projects have avoided the need for approval (i.e., the cumulative impact of small projects is not addressed).

- Mitigated Projects – new or significantly expanded development that is likely to result in permanent, adverse environmental or community impacts that can be mitigated, as determined by the department responsible for river valley strategic planning are exempt.[17] This exemption leaves the question of whether permanent, adverse impacts can or cannot be mitigated by staff (rather than the City Council) and shields the decision-making process from public knowledge and scrutiny.

Ambiguity of the “Public Interest”

Like its predecessor, the Draft ARP does not establish a clear baseline for environmental protection to govern development decisions. The Draft ARP requires the City Council to consider, among other things, whether development subject to a strategic assessment is in the “public interest”. However, there is no meaningful guidance as to what this means or which interests should prevail. For instance, does the “public interest” require prioritizing environmental protection? Economic gain? The Draft ARP sets out objectives but does not establish a hierarchy. Establishing a clear baseline for environmental protection would better ensure that the Draft ARP protects the river valley from unnecessary development as intended.

The Problematic Mitigation Hierarchy

The Draft ARP outlines a mitigation hierarchy to apply to projects, but it is underdeveloped and there are no details regarding how it should be effectively implemented. The mitigation hierarchy mandates that, when planning projects, developers aim first to avoid environmental damage. If avoidance is not feasible, then they must minimize the damage. Finally, if the damage cannot be minimized, they must restore or offset the damage.[18] Avoiding or minimizing environmental harm is possible, although only avoidance achieves the Draft ARP’s purpose of preserving the environment. In practice, restoration is only possible for temporary developments and is not applicable to any permanent construction.

However, the offset portion of the hierarchy is most concerning. There is a finite amount of land in the river valley. Offsetting requires either the acquisition of a new parcel of land to set aside or the protection of lands within city control that would not otherwise be protected. Developing portions of the river valley, even while protecting others through offsets, results in a net loss of undeveloped land. This outcome is fundamentally at odds with the Draft ARP’s goal of preserving the river valley, as is protecting lands outside of the river valley or the Draft ARP boundaries.

In the absence of specific guidelines explaining what constitutes minimization and establishing a framework for effective offsetting, this mitigation hierarchy may be used to facilitate development rather than conservation. Alternatively, a well-developed mitigation hierarchy can discourage environmental harm if offset ratios are high enough. For example, if land developers must conserve 3-5 times the amount of land they are developing, the environmentally detrimental development may no longer be worthwhile (especially financially and/or logistically).

Conclusion

The Draft ARP is a significant improvement upon the existing ARP. Nevertheless, the preservation of extensive discretion under the Draft ARP gives rise to risks that conservation efforts may be easily undermined. With a more prescriptive River Valley ARP, where discretion in decisions is narrowed, the City Council would be required to amend the bylaw if they desired to approve an environmentally detrimental project. This is the recommended approach as contentious decisions regarding development in the river valley should be subject to the fulsome public scrutiny that a bylaw amendment would entail. On the other hand, excessive discretion means less scrutiny and reliance on judicial review as an accountability mechanism. The Draft ARP would be stronger if it were clear when a project requires approval, what projects cannot be approved, and what the City Council should prioritize when making approval decisions.

Simon Robertson held a 2024 summer research position at the ELC.

Cover Image by Marcel Schoenhardt(May 2010), Edmonton River Valley, looking towards Saskatchewan Drive and the U of A.

THANKS FOR YOUR SUPPORT

Your support is vital for stronger environmental legislation. As Alberta’s leading environmental charity, the Environmental Law Centre has served our community for over 40 years, providing objective guidance on crucial legislative changes. Your contribution helps protect our environment for future generations.

Please support our work: Share, engage and donate to the ELC

[1] City of Edmonton, Bylaw No 7188, North Saskatchewan River Valley Area Redevelopment Plan (Feb 1985); for an updated map of the North Saskatchewan River Valley and Ravine System, see City of Edmonton, North Saskatchewan River Valley Area Redevelopment Plan Draft (June 2024), Map 2: Future Land Use Concept.

[2] City of Edmonton, North Saskatchewan River Valley Area Redevelopment Plan Draft (June 2024).

[3] Supra note 1 at s 1.4.

[4] Edmonton River Valley Conservation Coalition Society v Council of the City of Edmonton, 2022 ABQB 11 at paras 33, 53, 56.

[5] Supra note 4 at para 53.

[6] Ibid at paras 56-57.

[7] Supra note 2 at 3.0.

[8] Ibid at s 4.1.1 & 4.1.3.

[9] Ibid at s 4.1.6-4.1.7.

[10] Ibid at s 5.1.2.

[11] Ibid at Appendix 1: Strategic Assessment and Environmental Assessment Framework at 17.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid at s 5.2.3.

[14] Ibid at s 5.2.4.

[15] Ibid at Appendix 1: Strategic Assessment and Environmental Assessment Framework.

[16] Ibid at s 6.0.

[17] Ibid at s 5.2.3.

[18] Ibid at s 6.0.