Inside this blog

- A review of native grasslands in Alberta, including its history, threats, and importance.

- A look at regulatory guidelines and policies for grassland conservation, management and land use planning.

- Policy recommendations.

Native grasslands are “among the most threatened ecosystems in North America”.[1] This is despite their immense value as habitat, carbon sinks, and biodiversity hotspots. Although Alberta has a collection of policies and guidelines relating to native grasslands conservation and protection, we lack a comprehensive grassland policy. The overarching theme is to avoid disturbing grasslands if you can and if you cannot, then minimize and mitigate the damage. However, this approach is not evenly applied by our provincial decision-makers and not always in an enforceable manner. Alberta needs a native grasslands policy that comprehensively addresses risks and sets clear strategies specific to grassland ecosystems, and that is applied throughout Alberta by its regulatory decision-makers.

Grasslands in Alberta: An Endangered Ecosystem

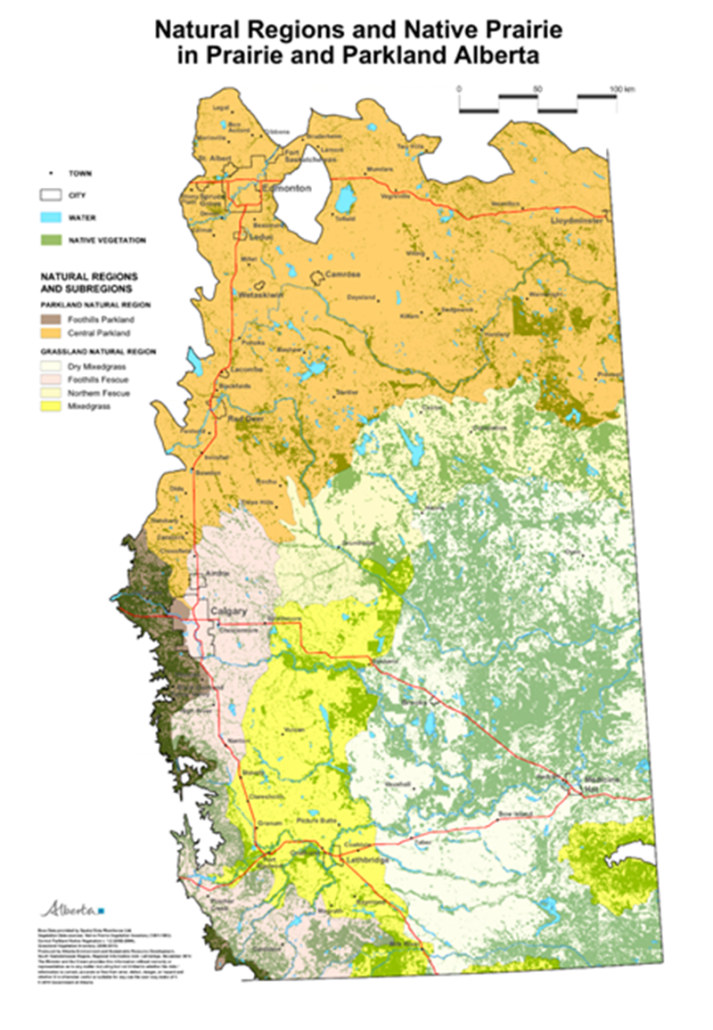

Most of Alberta’s native grassland ecosystems are found in the Grassland Natural Region and the Central Parkland Natural Subregion of south-east and east-central Alberta. Native grasslands also can be found in the Foothills Parkland and Montane natural sub-regions, along with some “remnant sites” in the Peace River Parkland.[1]

The ecological services provided by native grasslands are numerous including water regulation, climate regulation, carbon sequestration, air quality regulation and pollination services.[2] Native grasslands also have immeasurable value from a biodiversity perspective in that they are diverse and complex ecosystems that provide habitat for many species at risk.[3] The avoidance of both native and planted grasslands conversion has been identified as one of the most effective natural climate solutions for Canada.[4] Despite their immense value, grasslands are “among the most threatened ecosystems in North America”.[5]

What are the threats to Alberta’s Native Grasslands?

Soulodre et al. point out that in the Great Plains of North America (which includes the native grasslands of Alberta), the leading historical cause of native grasslands loss was agricultural conversion but more recently that has been replaced by oil and gas operations and mineral extractions.[6] According to Soulodre et al., “[e]xpansion of oil and gas infrastructure across the plains has exacerbated habitat fragmentation and pressures on biological diversity”.[7] The Prairie Conservation Forum (PCF) has specifically looked at the state of Alberta’s native grasslands, finding that loss was higher in those areas most suited for crop production and that irrigation expansion has facilitated the conversion of grasslands to croplands.[8] The PCF also found that impacts from industry, roads and residential housing expansion have contributed to loss of native grasslands in Alberta (especially closer to large population centres).[9]

So, how are these threats managed in Alberta?

Although the Wilderness Areas, Ecological Reserves, Natural Areas and Heritage Rangelands Act does allow for the creation of a type of protected area called heritage rangelands (which are protected grasslands which are actively managed using grazing activities), the majority of grasslands conservation and management considerations arise in the context of decision-making around land use planning and activity regulation. In terms of land use planning on public lands, the primary decision-maker is the Government of Alberta (as owner and manager of the land). On private lands, land use decisions are primarily left to the landowner but municipal decisions around land use planning and development may impose restrictions on private land use. Land use decisions on private lands are also impacted by provincial or federal legislation and common law requirements which may restrict the use of private lands. When it comes to activity regulation, regulatory decision-makers – such as the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER), the Alberta Utilities Commission (AUC), and the Natural Resources Conservation Board (NRCB) – play a key role in avoiding (or enabling) loss and fragmentation of native grasslands.

Grasslands and Land Use Planning Decisions

The opportunities for grassland management in land use planning decision-making differ for public and private lands. On public lands, grassland management primarily occurs through the operation of the Public Lands Act which manages access to and use of public lands through a variety of licenses, permits and other statutory authorizations. Because public lands are owned by the government, there is a great deal of governmental control over how those lands may be used.

While there is less direct governmental control, the use of private lands is not completely unrestricted. Municipalities have planning and development authority under the Municipal Government Act which can operate to place restrictions on the use of private lands. As well, provincial legislation regulating industrial activities or providing environmental protection places restrictions on the use of private lands (as do common law requirements which protect against things like nuisance and trespass).

Regardless of whether land is public or private, the Alberta Land Stewardship Act and its regional plans apply. This means that decision-making by regulatory bodies is guided (and in some circumstances constrained) by the provisions of an applicable regional plan.

Grasslands and Activity Regulation Decisions

There are several pieces of legislation that regulate activities in the province usually on a sector-by-sector basis. The general structure of this type of legislation is to restrict activities unless a statutory authorization is obtained, at which point the activity may be conducted. The general thrust of this legislation is to allow the activity to occur while imposing conditions or requirements to avoid, minimize or mitigate harm to the environment and public health. It is possible to impose conditions and requirements to specifically address impacts to native grasslands.

Grassland-Specific Guidance and Policy Documents

Numerous policy and guidance documents that encourage avoidance of native grasslands and minimal disturbance of grasslands by industrial activities have been published by the Government of Alberta (see Government of Alberta website). The general thrust of these documents is to encourage avoidance of native grasslands, and where native grasslands cannot be avoided taking steps to minimize and mitigate impacts to native grasslands. Some public lands are subject to Crown Land Reservations (previously called protective notations) which restrict activities in some way and may exist to protect grassland values. However, the province lacks an overarching grasslands policy that establishes conservation goals and outcomes (such as “no net loss”), addresses risks, and set strategies specific to grassland ecosystems.

How are these policies applied by decision-makers in Alberta?

As mentioned, without an overarching grasslands policy, the result is that protection and conservation of native grasslands is meant to be achieved through a collection of guiding principles and management practices which may be unevenly applied throughout the province. Alberta’s regulators – such as the AER, the AUC and the NRCB – are in a position to assess the potential impacts of a proposed activity on native grasslands. They can make decisions which respect the policy to avoid conducting activities on native grasslands, and to impose conditions on statutory authorizations to otherwise protect native grasslands (and such conditions may be made enforceable).

The ELC has a forthcoming report that looks at grasslands considerations in decisions made by Alberta’s regulators. Grasslands considerations are often raised in the context of AUC hearings for renewable energy developments (which to date only occur on private lands). Over time, the AUC has shown increasing willingness to modify proposed projects to ensure native grasslands are avoided, including in some cases requiring proposed infrastructure to be re-sited off native grasslands and imposing conditions designed to monitor and protect native grasslands (often due to it being valuable wildlife habitat).

The AER considers applications for oil and gas operations on both private and public lands. The vast majority of the AER’s decision-making is essentially automated. Unless there is an objection or some other concern, applications are processed on a routine basis, meaning the statutory authorization issues persist as long as an application is complete and satisfactory. Non-routine applications may trigger a hearing which ultimately results in a written decision report. For this reason, a complete picture cannot be seen by looking only at written decision-making.

Having said that, it generally seems that on private lands, the AER leaves surface matters to negotiation between the landowner and the operator. That is, on private lands, any grassland concerns would be a matter of contract such that the landowner could request certain operational restrictions for avoidance, weed control and so forth but this is done without the involvement of the AER. In cases where agreements cannot be reached, the Land and Property Rights Tribunal (LRPT and formerly, the Surface Rights Board) may be turned to address compensation and other surface concerns. However, there is little indication that grassland conservation and protection are significant factors in LPRT decisions.

On public lands, the AER seems to rely heavily on the Master Schedule of Standards and Conditions (MSCC).[10] While the MSCC was originally published in 2017, it is a consolidation of previous departmental documents, which in themselves were consolidations of pre-existing guidelines, which means some form of the MSSC standards and conditions date back to before 2010.[11] These are standards and conditions which are prescribed by the Government of Alberta based upon location and type of activities. That is, within certain areas of public lands (including specified native grasslands locations), a variety of standards and conditions may apply to specified activities (an oil or gas well, a pipeline and so on).

A review of the AER’s written decisions reveals some inclination to impose conditions onto statutory authorizations with a view to protecting native grasslands. However, the AER does not always impose enforceable statutory authorization conditions but instead accepts that an operator has made commitments to undertake minimization and mitigation steps. This raises questions around enforceability as failure to meet a commitment is not a breach of a statutory authorization in the same way failure to meet a condition is. Where the AER does impose conditions related to grasslands protection, these tend to be related to weed control (i.e. specifying steps to reduce the spread of weeds to native grasslands), surface integrity (i.e. restricting activities to operations and timing to minimize disruption of soil layers), and habitat disruption (i.e. timing operations to avoid breeding of nesting birds). The AER does not seem to be inclined to deny an application on the grounds that an activity is proposed to occur on native grasslands.

What needs to change?

The overarching theme of Alberta’s approach to native grasslands conservation and protection is avoid disturbing grasslands if you can and if you cannot, then minimize and mitigate the damage. However, the current collection of policies and guidelines lacks clear conservation goals and outcomes, does not comprehensively address risks, or set clear strategies specific to grassland ecosystems. Furthermore, these policies and guidelines may be unevenly applied throughout the province and to all activities, and in an unenforceable manner. While reviewing the decisions made by Alberta’s regulators gives a sense of the priority of grasslands conservation and protection in the context of activity regulation, it does not convey information about the effectiveness of land use decisions made by the Government of Alberta and municipalities. Furthermore, while conditions may be imposed via statutory authorizations or the MSSC, on-the-ground research is required to determine if such conditions are actually effective in protecting and conserving grasslands.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””] If you are interested in more detail, keep an eye out for the ELC’s report on Grasslands and Regulatory Decision-Making which is coming soon!Subscribe to get custom updates for all our Fall releases. [/perfectpullquote]

As such, the ELC would like to see a comprehensive grasslands policy to address the continuing loss of grasslands and to maintain the biodiversity of these important landscapes and carbon sinks. Tyler J. Lark has proposed that two possible goals for native grassland conservation are “no prairie conversion” and “no net loss of grasslands”.[1] As explained by Lark, the first aspires to complete prevention of any future conversion of native grasslands to croplands, development or otherwise. Lark acknowledges that this benchmark may be unattainable, but it does establish a clear objective which is straightforward for policy alignment. According to Lark, the second is a more realistic goal as it aims to maintain the current total area of native grasslands thereby allowing for loss of native grasslands to be compensated by addition of grasslands elsewhere. As pointed out by Lark, these goals need not be mutually exclusive, they can be used together in a single conservation framework, specific areas can be identified as zones for no conversion and no net loss of native grasslands. Further work is required to determine whether a policy of no net loss of grasslands would be appropriate and effective in Alberta in light of issues around the ability to replace and reclaim grasslands (for example, it is known that reclamation of rough fescue grasslands is typically unsuccessful).

In addition to a comprehensive grasslands policy, thought should be given to the concept of threatened landscape legislation which enables ecosystem-based protection. For example, Nova Scotia’s Biodiversity Act[2] enables establishment of biodiversity management zones on both public and private lands. An alternative would be renewed commitment to complete regional planning under the Alberta Land Stewardship Act including environmental management frameworks which set biodiversity goals and thresholds.

THANKS FOR YOUR SUPPORT

Your support is vital for stronger environmental legislation. As Alberta’s leading environmental charity, the Environmental Law Centre has served our community for over 40 years, providing objective guidance on crucial legislative changes. Your contribution helps protect our environment for future generations.

Featured photo by David Thielen from unsplash.com

[1] Tyler J. Lark, “Protecting our prairies: Research and policy actions for conserving America’s grasslands” (2020) 97 Land Use Policy 104727.

[2] Biodiversity Act, NS 2021, c. 3.

[1] Cheryl Bradley and Marilyn Neville, Minimizing Surface Disturbance of Alberta’s Native Prairie: Background to Development of Guidelines for the Wind Energy Industry (Lethbridge, AB: Foothills Restoration Forum and Prairie Conservation Forum, 2010)

[2] Yuanyuan Zhao, Zhifencg Liu, and Jianguo Wu, “Grassland ecosystem services a systematic review of research advance and future directions” (2020) Landscape Ecol. 35: 793.

[3] Edward Bork and Pascal Badiou, The Importance of Temperate Grasslands in the Global Carbon Cycle (Edmonton: 2017, Ducks

[4] C. Ronnie Drever et al., “Natural climate solutions for Canada” (2021) 7 Sci. Adv. Eabd6034.

[5] Etienne M.J. Soulodre, Amalesh Dhar, and M. Anne Naeth, “Plant community development trends on mixed grass prairie well sites 5 years after reclamation” (2022) 179 Ecol. Engineering 106635 at page 1.

[6] Etienne M.J. Soulodre, Amalesh Dhar, and M.Anne Naeth, “Plant community development trends on mixed grass prairie well sites 5 years after reclamation” (2022) 179 Ecol. Engineering 106635.

[7] Etienne M.J. Soulodre, Amalesh Dhar, and M. Anne Naeth, “Plant community development trends on mixed grass prairie well sites 5 years after reclamation” (2022) 179 Ecol. Engineering 106635 at page 1. Also see M. Anne Naeth et al., “Pipeline Impacts and Recovery of Dry Mixed-Grass Prairie Soil and Plant Communities” (2020) 73:5 Rangeland Ecol. & Mgmt. 619.

[8] Karen Raven et al., Occasional Paper #6: The State of Alberta’s Prairie and Parkland: Implications and Opportunities (Lethbridge, AB: 2022, Prairie Conservation Forum).

[9] Ibid.

[10] Government of Alberta, Master schedule of standards and conditions (Edmonton: 2024, Government of Alberta) available online: https://open.alberta.ca/publications/master-schedule-of-standards-and-conditions.

[11] See prefaces to the 2017 version of the MSSC, online: https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/133e9297-430a-4f29-b5d9-4fea3e0a30c2/resource/04c0806b-dcb2-41f7-b703-1b662ea318ff/download/masterschedstandardsconditions-jun28-2017.pdf and Alberta Energy Regulator and Alberta Government, Integrated Standards and Guidelines, Enhanced Approval Process (Edmonton: 2013, Government of Alberta), online: https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/633dc6c2-8b96-4602-bbf0-f1bd40437ae9/resource/feddfcb8-d81d-4011-8247-59b1f5b162c6/download/2013-enhanced-approval-process-eap-integrated-standards-guide-2013-12-01.pdf.

[1] Etienne M.J. Soulodre, Amalesh Dhar, and M. Anne Naeth, “Plant community development trends on mixed grass prairie well sites 5 years after reclamation” (2022) 179 Ecol. Engineering 106635 at page 1.